The Price of Potential

A Look into the Predatory Purpose of For-Profit Schools

Jessica Graham

November 28, 2022

“I thought that college would be my way out of poverty, little did I know I would end up being worse off than my mom was at my age.” Jennifer Lezan, a first-generation Latina, has become an activist in her community—fighting against predatory student loan debt after having experienced it herself. On her YouTube channel, Jen tells her story to educate and help those who may be facing similar constraints. In her own words:

I grew up in poverty on the west side of Chicago, with a single mother and a younger brother. I don’t know who my biological father is, and my brother’s dad and my mom split when we were really young. When I say I grew up in poverty, I mean late rent, hot water and lights being turned off, having to pick bills over groceries kind of poor. One memory that I will never forget, and excuse me if I get a little emotional on this, but one memory that I will never forget is when our family had to steal groceries in the late 90s. I remember after that incident I was so angry at my mom that she would do that, and then I was mad at how much she worked at the new job that she had gotten shortly after. As an adult with children, I understand now. I can’t even imagine having to be in her shoes at that point and goodness knows what would have happened if she had been caught and arrested.

Photo of Jen Lezan, found on her profile on the Project of Predatory Student Lending’s website.

Seeking a different life, Jen worked multiple jobs, getting experience in the creative industry with the dream of working professionally in that sector. However, her family life at the time was not suited to this focus, with the presence of gangs and abusive boyfriends in the house. As she explains it, “at 17 years old I moved out on my own. I didn’t drop out of high school, in fact, I had been working so hard at school on top of my evening and weekend job that I managed to graduate high school six months early. That very year, I had also been recruited by what is now known as a for-profit college, who sold me lies about their 99% job placement after graduating. Thinking that my dreams to attend art school and pursue a creative career were well on their way, I decided to go to that school.”

For-profit colleges and universities capitalize on recruiting ‘nontraditional students,’ whether they are marginalized students, working professionals, single parents, veterans, or any number of other communities the institution deems ripe for exploitation. By promising advanced education with flexible schedules, these institutions practice “predatory inclusion”—providing an opportunity to those who have been historically excluded, but under circumstances that make it nearly impossible to achieve the promised benefit. In a way, this strategy maintains but shifts the feeling of having little-to-no control over their life. As Jen explains, for her and others, “[d]ebt is more than a trap—it’s literally a form of social control.” Jen left her family’s house to seek control over her own well-being, only to be met with the harsh reality of educational greed. For-profit institutions are purposefully increasing the racial wealth gap and doing so with federal government funds.

“Debt is more than a trap—it’s literally a form of social control.”

For-profit institutions are distinct from both public and private nonprofit institutions. While public and nonprofit institutions (theoretically) are not in the business of making money, for-profit institutions are designed for that exact purpose. Though all three generate revenue, the difference is where that revenue is supposed to go. In for-profit institutions, the answer is simple: the owners’ pockets. Many for-profit institutions are “publicly traded, nationally franchised corporations legally beholden to maximize profits for their shareholders.” We’ll delve more into the consequences of this later, but the key point is that for-profit educational institutions are traded on stock markets in the same way as major corporations, such as Amazon or Exxon. Thus, the success of the school is directly tied to its profitability rather than its graduation or employment rates.

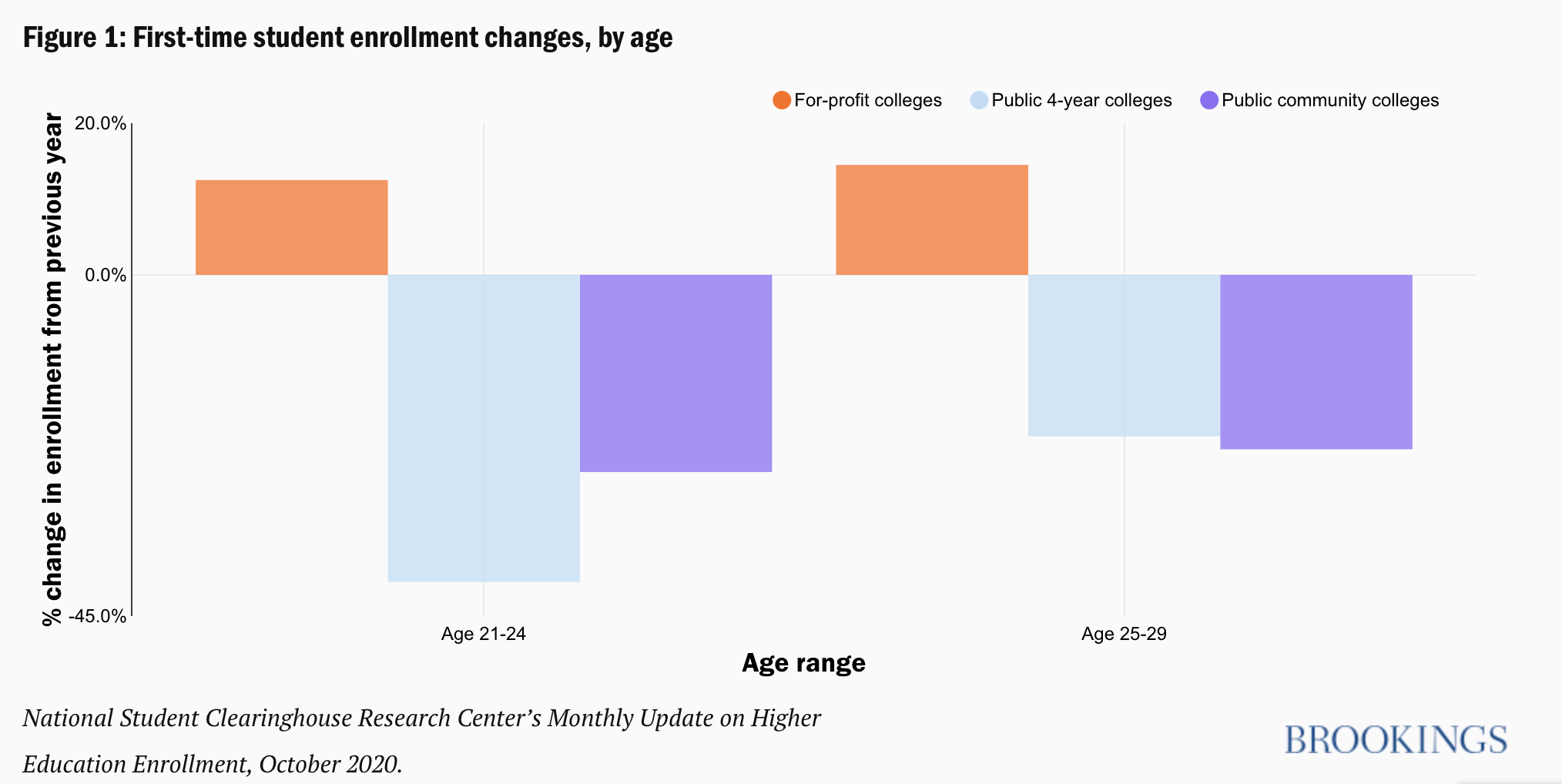

The profitability of these institutions is directly tied to the percentage of their students who take out loans. The business model of most for-profit colleges relies directly on “federal student loan dollars for revenue and profit.” Since they need more federal loan money, they recruit more students who will need to take out federal student loans. The structure became so pervasive that the federal government added clarification in its legislation that for-profit institutions could not get 100% of their revenue from federal student loans. That change, though, is less than impressive, as the cap now sits at 90%. As shown in the graph below, many of the largest for-profit colleges come very close to reaching that limit:

Source: The Brookings Institute

By the time she graduated, Jen was, as she described it, financially worse off than she had been before attending college. In her words, “when I graduated, I was about eighty thousand dollars in debt—and that ballooned to over ninety thousand due to compounding interest over the years. The interest alone on these loans is highway robbery.” In an interview with the Project on Predatory Student Lending, Jen describes the impact this debt has had on her mental and emotional health: “I was making minimum wage when I graduated and there was no way I was going to be able to pay off this debt. During the first few years, I went through a lot of mental health issues because of the debt. I still struggle to make ends meet. I can’t buy a house with my debt-to-income ratio. I had these big dreams of the things I wanted to do in the world, and they were crushed.”

In order to profit from federal loans, for-profit institutions target students who they determine would need the maximum amount of financial aid. In an interview, Eileen Connor, the Director of the Project on Predatory Student Lending, explained the methods she has seen first-hand: “The content of this advertising and the branding and all of that is probably so much more expressly cast in racialized terms than you would even expect. It’s just not… it’s not veiled and it’s not subtle, it’s just there. That is what it is. And then, in terms of the placement, oftentimes what you’ll see is … basically the lead generators who are going to place the ads and deal with the inquiries from it, they are by zip code. And they’ll calibrate it, so, you know, they’re getting too many from this area so turn off this ad and that zip code as of this date and turn it on in this one… It’s just cut and dry.”

“If you lived in a certain zip code, you would never even know these schools exist, whereas if you lived in another zip code, you would think that they are just everywhere.”

For example, Corinthian College, which is no longer in operation, spent over $600,000 for just two weeks of advertising on Black Entertainment Television (“BET”). As the table below shows, these predatory practices have been successful in convincing students of color to take out more federal loan funding:

Source: Center for American Progress

Out of all students at for-profit institutions, 89% took out student loans. This rate is even higher for Black students (95%). These statistics don’t even account for the size of these students’ loans. Tuition at some for-profit institutions is twice as expensive as at Ivy League colleges. For context, the current cost of attendance at Harvard College is approximately $80,000 per year. Even though the costs are astronomical, at for-profit institutions most of this money doesn’t even go to properly educate students. Research shows that less than a quarter of the money students take out in loans actually goes to their education. This means that students at for-profit institutions are paying more than Ivy league students, and are just lining the pockets of executives and shareholders.

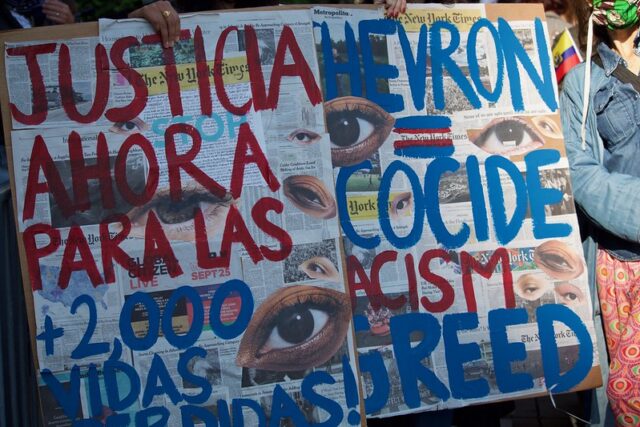

Though Black and Latinx students make up less than a third of all college students, they account for half of all students attending for-profit institutions. This is, again, because of the methods of advertising and targeting implemented by for-profit colleges. As articulated by the Project on Predatory Student Lending, “[b]ecause the industry targets its worthless products in explicitly racial terms, the debt associated with for-profit colleges is not only predatory, it’s racist.” The Millennial Student Debt Research Project highlights the racial disparity between wealth and student debt:

Source: Millennial Student Debt Research Project

Pulling these students in, though, isn’t enough. After securing students’ tuition money, these institutions continue prioritizing profit by dragging out the curriculum, providing no job-hunting assistance, or any other number of tactics designed to keep students in school longer. The longer they’re in school, the more loans they will need, and the more profit the institution will receive. Thus, for-profit colleges have the lowest graduation rate of all higher education institutions.

The statistics are shocking: only 22% of first-time, full-time bachelor’s degree students will graduate within six years, compared to 55% at public institutions and 65% at private nonprofits. The 22% graduation rate is only the average—some institutions are much lower. Out of the University of Phoenix’s online students, only 5% graduated within six years. Once for-profit universities pull their students in, they leave them out to dry. In fact, most students who are lucky enough to graduate from these institutions do significantly worse while job hunting than counterparts with only high school degrees.

Jen was in a particularly difficult situation when she graduated:

“This is also the year that my oldest daughter was born. Everyone assumed that I would drop out because I was pregnant, and instead I graduated at the top of my class. I also graduated from one of the worst economies. This is right when the mortgage bubble burst in 2008 … finding a job in the creative industry and marketing was harder than ever, so I hustled. I worked retail, I managed to freelance on top of it all, trying to build up my design and marketing portfolio, often taking on free work. Paying my student loans had become difficult, often having to argue with the student loan servicers that my income was not high enough to pay the nearly two-thousand-dollar bill that it all came out to. No one ever informed me that I could apply for something like the income-based repayment plans, or that I could consolidate my debt or fight for a lower interest rate, or that some of the loans that I was told were flat rate were actually adjustable rates that kept increasing and going up and up and up over the years so it would make more sense to try and refinance. But of course, why would they do that? It was this year that I learned to fight back.”

“It was this year that I learned to fight back.”

Once the institution has squeezed out enough money from its students, they’re left to their own devices. Some may graduate and go on to work jobs that can’t even compare to the opportunities they were promised, others don’t graduate at all. Either way, most of these students are left with mountains of debt and no way to pay it off. Of those students who do graduate, 96% of them are left with double the amount of debt of their public or nonprofit counterparts.

Those who do not graduate are left in a similar position. With worse job prospects and more debt, students graduating or dropping out of for-profit institutions have a greater likelihood of defaulting on their loans. As noted by Brei’a Womack, “[f]or-profit schools and the Department of Education have also made it harder for students to repay their education debt because debt repayment regulations, enacted by the government, tend to work in favor of corrupt corporations, like for-profit colleges, rather than students.” The reality of this, as Jen explains, is that “[i]t really pushes this idea so many of us were sold about upward mobility—the idea has been, and always will be, an illusion. While leveraging debt has lifted some out of poverty, things like credit access were a cornerstone policy that helped create the white middle class. Most people, especially people from the BIPOC community, were left behind or pushed into inescapable predatory contracts.” After exiting an institution designed to use them for profit, these students enter a repayment system designed to help that very institution.

“It really pushes this idea so many of us were sold about upward mobility—the idea has been, and always will be, an illusion. While leveraging debt has lifted some out of poverty, things like credit access were a cornerstone policy that helped create the white middle class. Most people, especially people from the BIPOC community, were left behind or pushed into inescapable predatory contracts.”

For federal loans, a person (or “borrower”) “defaults” if they fail to make payments for 9 months. After default, the borrower is then usually referred to private collection agencies, which tack on fees that add years to the borrower’s loan repayment process. Borrowers also face the possibility of action from the federal government—such as the seizing of wages, Social Security, or tax refunds—without any statute of limitations (the “law that sets the maximum amount of time that parties in a dispute have to initiate legal proceedings”). A single fact—a default, which was likely out of their hands in the first place—could remain a sense of impending doom for the rest of their lives. The likelihood of this is not insignificant. Out of students who dropped out of for-profit institutions, 62% of them, on average, defaulted. This number is even higher for Black students, with 3 out of every 4 of them defaulting.